Communication is a two-way street. This is no different for people who communicate using AAC than for anyone else. We can’t simply hand a user a communication system with a robust vocabulary and expect them to use it out of the box. If we want someone to become a successful communicator, both they and their communication partners must put in time and effort developing communication skills.

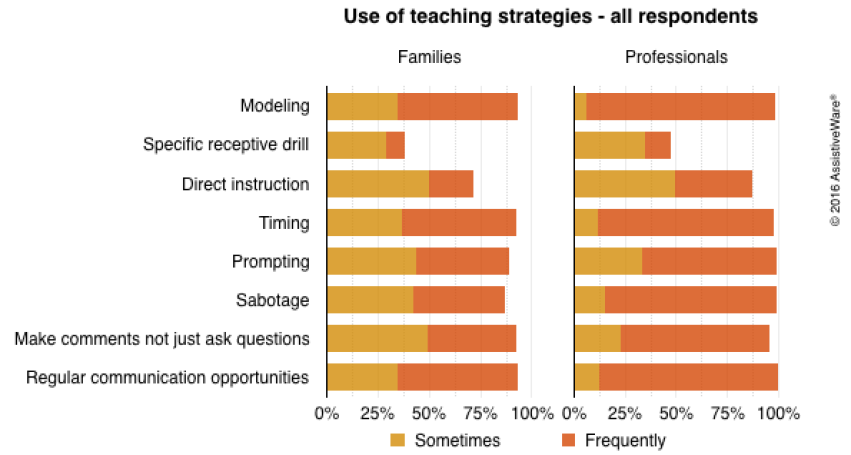

For family members, therapists, and teachers supporting early AAC users in learning communication, good teaching skills are a must have. In this post, we’ll take another look at the results of last year’s International AAC Awareness Month Survey to see what it tells us about the teaching strategies that family members and professionals use to support people who use AAC.

Strategies considered

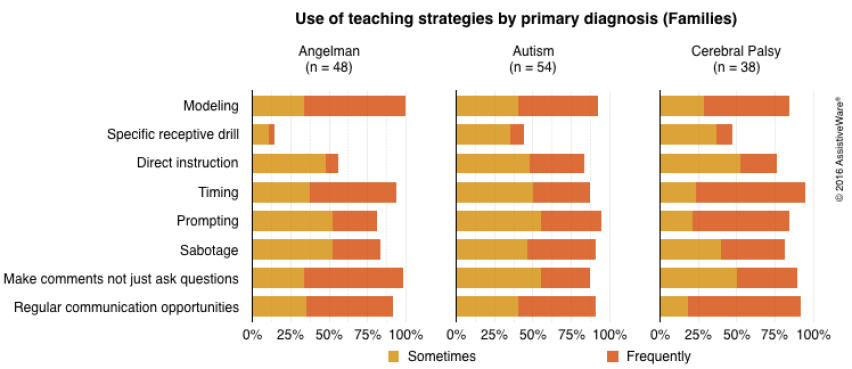

We asked the respondents to report how often (rarely/never, sometimes, or frequently) they use eight different strategies when interacting with their family member or working with clients:

- Modeling: demonstrating use of the AAC system for communication

- Specific receptive drill: asking the user where to find something on their system (e.g. "Find ‘cookie.’”)

- Direct instruction: specific and explicit teaching of individual words

- Timing-based strategies such as giving more time for the user to respond and expectant pauses

- Prompting (visual, verbal, or physical)

- Sabotage: setting up situations that require the user to communicate in order to participate in an activity or receive an item (e.g. placing items out of reach)

- Making comments rather than always asking the user to answer questions

- Providing regular and reliable communication opportunities within functional day-to-day activities

Ideally, we would hope to see high use of strategies that model and promote use of the AAC system in the context of everyday activities and take advantage of natural communication opportunities. If we want the user to become a skilled communicator, we need to make sure they have plenty of opportunities to see and practice communicating the things that we hope they will one day be able to say more independently. In contrast, we would hope to see lower use of strategies that put the user in a more passive role, where the teacher instructs him or her on what to say. In terms of the specific strategies, this means higher use of modeling, timing-based strategies, and the last two communication partner strategies and lower use of specific receptive drill and prompting.